Penn State recently a Wikipedia Edit-a-thon held in conjunction with Art+Feminism's national program, and I gave a talk called "Crowdsourced Narratives & Participatory Art." The following is an adapted version of that talk, examining the history of participatory art and technology, and how it intertwines with pop culture.

Earlier this week, the showrunners of HBO's Westworld, Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, revealed the punchline of an epic prank played on their fans. It began earlier in the day with a bewildering plan to reveal the entire plot of the show's upcoming second season to diehard fans on Reddit—an apparent effort to spoil the plot themselves, after fans infamously figured out the big twist of season one way ahead of time. While it turned out to be a delayed April Fool's joke, the plan ignited debate around the web about the nature of spoilers and the relationship between fans and creators.

Westworld has stoked the obsession of its fans before, by hiding puzzles in marketing materials and engaging with fans on Reddit. It's often expected that directors, writers, and musicians will engage their fans on Twitter and other platforms, with increasingly mainstream conventions serving as the ultimate interface between fans and the creators that inspire them. It's gotten to the point where fans are exerting their influence over the content the consume. While promoting Pacific Rim: Uprising, actor Charlie Dey explained that not only was he aware of fans' shipping of his character Hermann and co-star Burn Gorman's Newt, but he brought it onto the screen. The characters are nominally friends, but that hasn't stopped fans from imagining the two as lovers, a relationship that Dey says is "so much more interesting." He told a reporter, "it completely informs the character. I honestly was thinking about it that way when I was acting through those scenes."

Elsewhere in the media landscape, fans of the CW's Supernatural have successfully lobbied for a spinoff based on some of the show's popular female characters called Wayward Sisters. Supernatural is almost comically masculine with it's vintage cars, gruff protagonists, and road-tripping Americana, so it's no wonder that most of the show's fans are women. After thirteen seasons (!) of underwriting their female characters, and a failed spinoff about another set of macho ghost-hunters, the creators finally turned to their fans for inspiration. Wayward Daughters had already been conceived of as a fan dream-team composed of existing characters on Supernatural. There were fan artworks, fiction, and online discussions aplenty. Fans articulated their vision and seemingly willed the show into existence.

Catering to fans can be seen as a marketing ploy, creating buy-in from potential viewers and leveraging online discussions as grassroots advertising, but it's also the result of a larger cultural emphasis on participation. The modern practice of empowering fans may have begun with Lord of the Rings, when Peter Jackson interfaced with fan "spies" that were stalking the production in New Zealand. As described in Chloe Galloy's wonderful 2012 history of fandom, "Gordon Paddison, the director of interactive marketing at New Line decided to connect with online fans of the Tolkien books and take their vision into account." Paddison described his approach as "being completely open and working with the fans," which led to Jackson's dialogue with fans and his concession to make "the filmic text... adhere more closely to the novels than had originally planned."

After multiple hobbit-based franchises and the nonstop growth of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the power of fans seems cemented in popular culture. Directors like The Last Jedi's Rian Johnson respond to individual fans on Twitter, and audiences take on the roles of critic and historian when they add to IMDB or Wikipedia. We're all content creators too, as the convenience of media tools continues to rise, and platforms like YouTube and Instagram distribute our ad-hoc creations around the world.

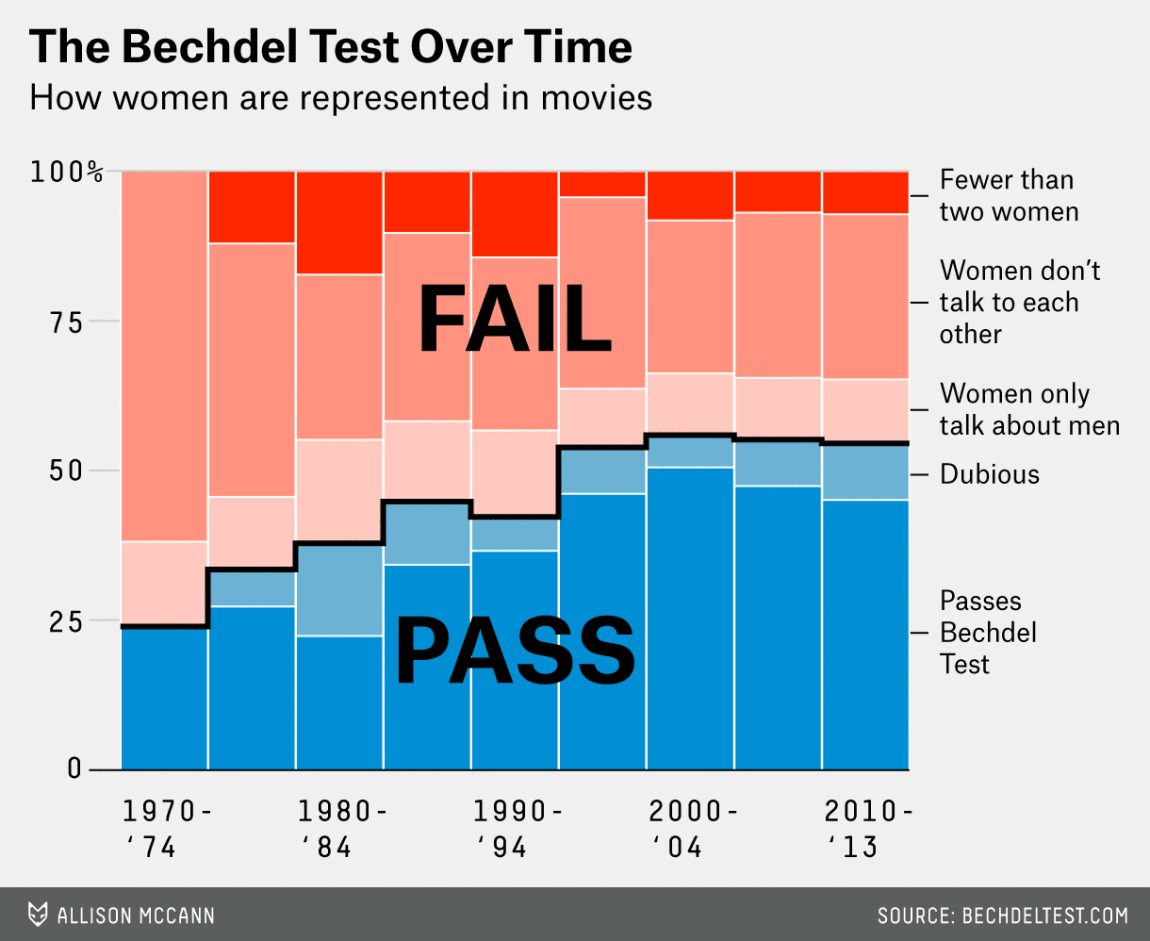

This democratic noosphere might be helping our culture progress beyond the politics of the Twentieth Century. With more diverse creators and traditional authors being held accountable to their work, representation in popular culture seems to be on the rise. Based on data collected from bechdeltest.com, Walt Hickey, writing for FiveThirtyEight, charted the rise of films passing the Bechdel Test since the 1970's. Like the fans of Supernatual, the consumers of movies, comics, and other media seem to be demanding not only changes to the stories of their beloved characters, but to our shared cultural narrative.

It's within this context that Nolan and Joy's surrender to r/westworld felt all the more believable. The idea that the creators' work belonged to the fans seemed plausible. If fans could be stewards of the show's secrets, then the creators would be protected from being scooped; they could exert a semblance of authorial control over the release of their content.

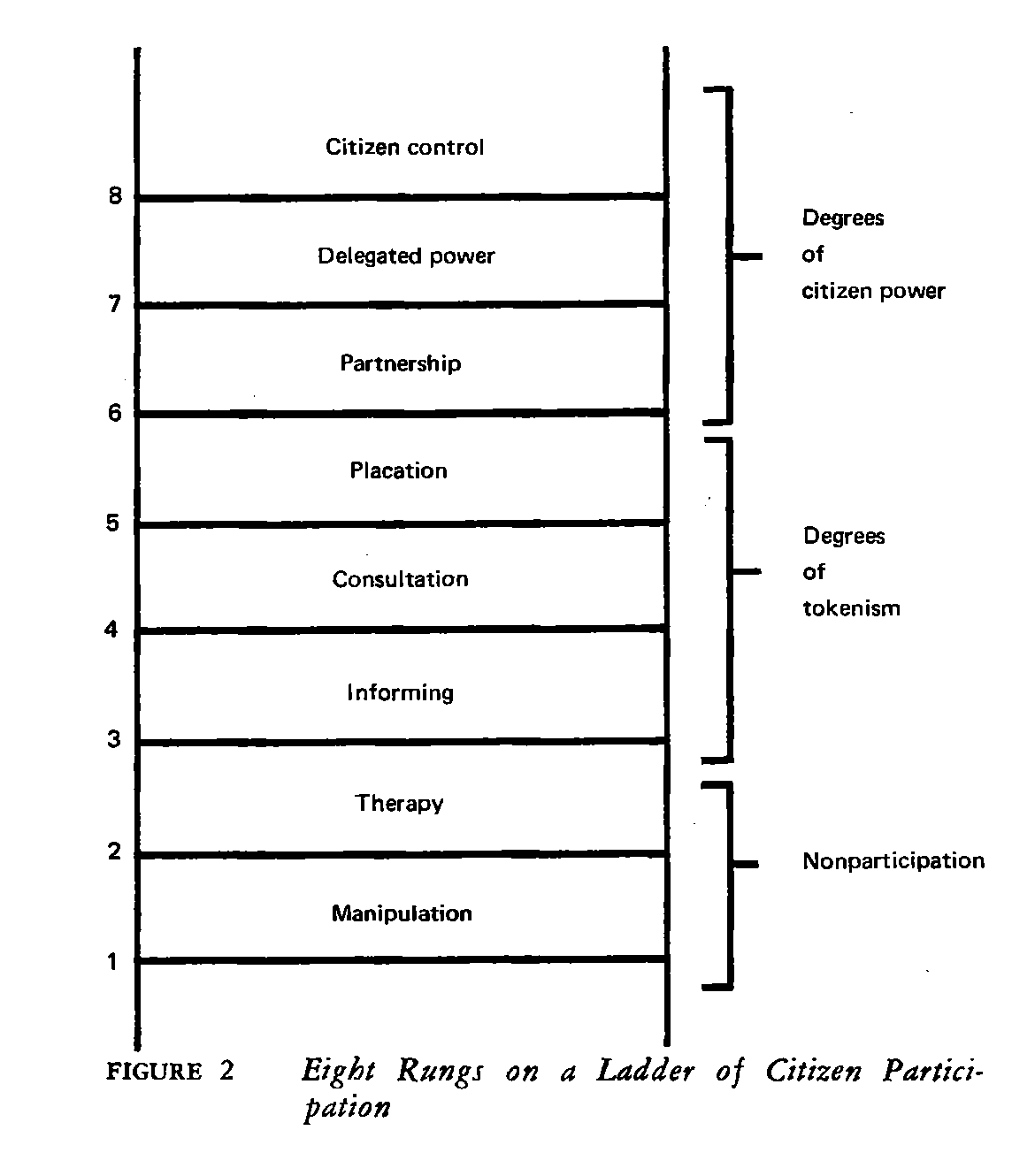

In discussing these examples of participatory fandom, it's helpful to consider a hierarchy of participation. American policy expert, Sherry Arnstein sketched one such device in 1969. Her "Ladder of Citizen Participation" described eight rungs of power, ranging from basic manipulation to complete citizen control. While conceived as a way to assess civic influence, Arnstein's ladder has been used to describe many systems of power such as economics, sociology, and art. It's fitting that Arnstein conceived of the ladder in the 1960's, when civic unrest dominated the United States, and American artists established the modern conception of participatory art.

I wouldn't blame you for being confused by the overlapping fields of instillation art, performance art, relational aesthetics, social practice, interactive art, and so on. These distinctions are fairly meaningless, and most artists don't worry about which box they fit into (I know I don't). So suffice to say, that there is a rich history of participatory art, or art that involves the viewer in an active way—whether it's pushing a button or building a sculpture.

Using Arnstein's ladder, a low level of participation might be an interactive object, like the sculptures of Lygia Clark, which users (to borrow a design term) wear and "manipulate" to create new sensorial experiences. Clark came from a painting background, and her wearables from the 1960's can be judged in a similar manner. Like audiences in a movie theater, the people wearing the objects are interchangeable.

At the top of the ladder, are artworks that don't exist without action from the audience. Marina Abromovich's Rhythm 0 (1974) demonstrates complete citizen control, not only because the performance relies on audience participation, but because the artist is literally at the mercy of strangers, held hostage to their desires. In the performance, Abromovich stood silently while participants used a variety of objects to interact with her; ranging from a feather duster to scissors to a gun loaded with a single bullet. Abromovich said she wanted to know “What is the public about and what are they going to do in this kind of situation?”

Most artists would not put themselves so directly at the mercy of their audience, indeed the creators of Westworld would be hard pressed to physically meet all of their obsessive fans, much less engage them in masochistic performance art. Luckily, modern technology allows nuanced participation at a distance.

In 1964, inventor-artist Gordan Pask conceived of a cybernetic theater where audience members could interact with the performance via analog electrical devices. He created many interactive, mechanical installations, but audiences in his theater would not only affect the appearance of the set and lighting, but essentially vote to determine the dramatic action on stage. Other early experiments in audience participation occurred in television and media, but it wasn't until the birth of cell phones and the web that audience voting became commonplace.

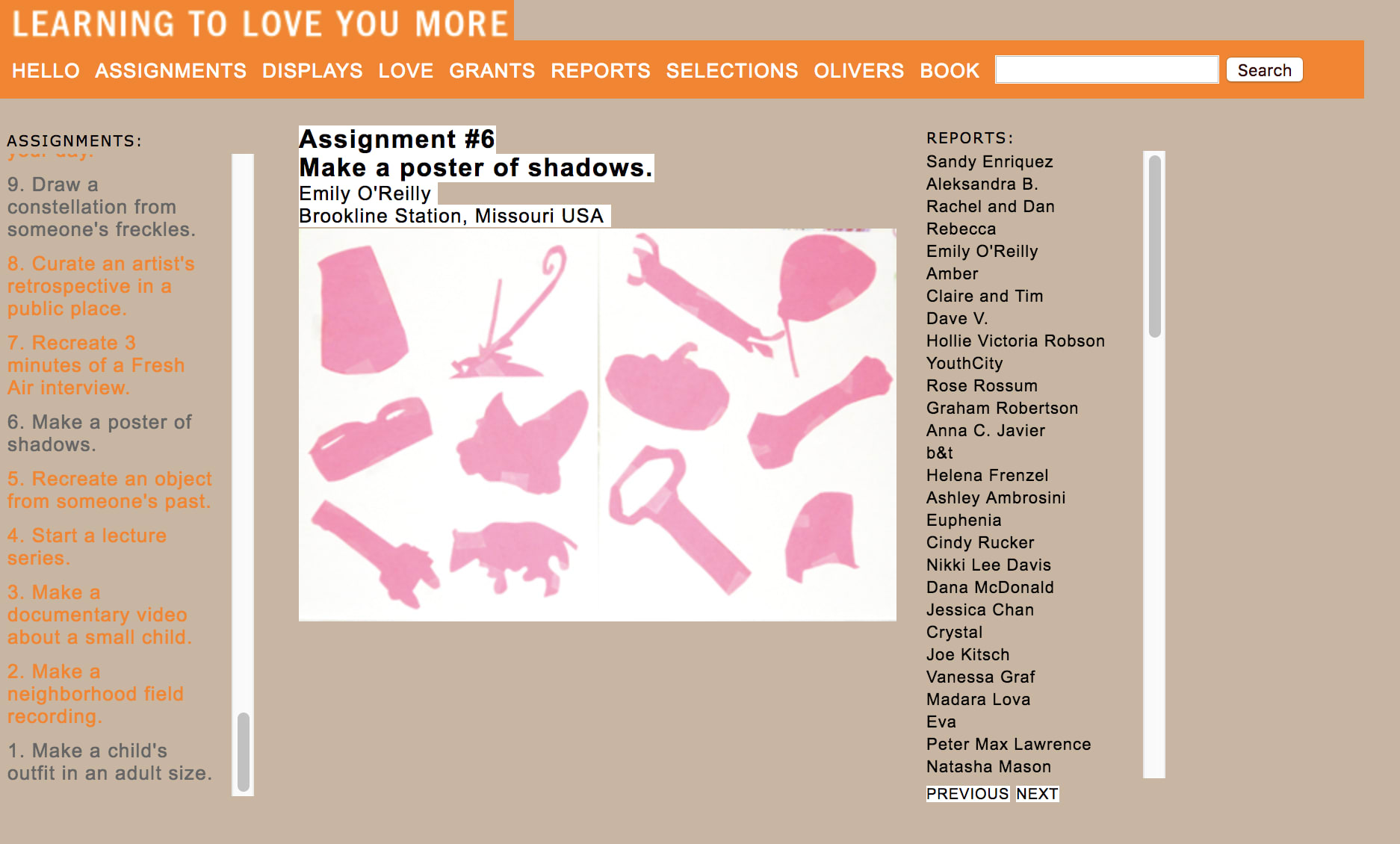

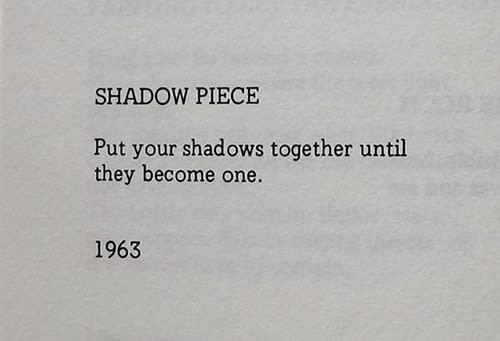

Artists pioneered some forms of participation, but they have also experimented alongside mass media, leveraging new technology for their own purposes like Pask and his interactive machines. During the rise of Web 2.0, artists Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher maintained a participatory website called Learning to Love You More, that invited readers to respond to conceptual art prompts like "recreate the moment after a crime" by uploading documentation of their efforts. Prompts like "make a poster of shadows" have explicit precedence in 60's conceptual scripts by artists like Yoko Ono. Whereas Ono published her work in books like 1963's Grapefruit, July and Fletcher leveraged the accessibility of the web to interact with a global audience. Their work also owes a debt to the more high-brow submission website DO IT curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist in 1993.

July continued to experiment with online platforms and participation with her 2014 app, developed in with Miu Miu, called Somebody. This app allowed users to send messages to each other by way of a third party, effectively sending strangers to recite messages to each other and create surreal social interactions. The app's success was mostly limited to densely populated areas of the artworld fans, but it hinted at the possibility of personal, nuanced participation in a traditionally automated service.

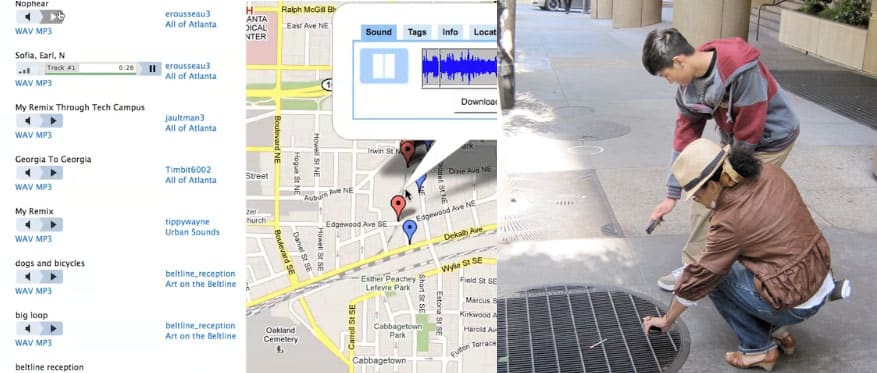

The capabilities and ubiquity of smart phones was also leveraged by a team of artists at the Georgia Institute of Technology to create Urban Remix. This roaming data project led by Jason Freeman, Michael Nitsche, and Carl Disao, invited participants to record samples of audio in specific areas and add them to an online database where they could be mapped and remixed to create an audio portrait of the area. One has to wonder though, how this democratic means of production can compare to the audio walks of Janet Cardiff, who also creates site-specific soundscapes. Cardiff's walks result from a single author speaking to a single listener, presumably showing a level of thoughtfulness and polish significantly beyond that of the average Urban Remix user.

Today's audiences expect a greater level of participation, and have used that power to create more diverse and democratic narratives in their stories. But creators can't rely entirely on the will of the people, especially online, as proven by incidents like the write-in suggestions for naming an antarctic ship Boaty McBoatface, which showed the hilarious but artless imagination of crowd-mentality..

The art world is also under the sway of participatory culture, as museums prioritize large-scale interactive experiences that risk turning institutions into theme parks. Carsten Holler's giant slides in the Tate Modern or Ann Hamilton's dramatic swings in New York's Armory are thoughtful works by individual artists, but they feed audience's expectations for surface-level participation where the user is interchangeable.

On the middle rungs of the Arnstein's ladder, artists offer limited control to their audience, adopting the role of host and inviting participants to contribute to the work in their own manner. Adrian Piper's Funk Lessons (1982–84) served as a successful model for socially engaged art, where Piper invited diverse groups of people to learn about funk music in a combination lecture/dance party. As the culturally loaded music and Piper's historical anecdotes paved the way for conversation, the artist receded into the background. Similarly, Antony Gormley's One & Other (2009) invited hundreds of participants to occupy the fourth plinth outside Trafalgar Square, and perform or behave however they like. These two works respect participants by granting them limited control and allowing their contributions to affect the final form of the artwork, albiet in brief or debatable ways. For a pop culture equivalent, consider the postmodern tapestry of Star Wars Uncut, which splits the film into 30 second segments, which are then recreated by fans around the world.

The tension between an individual voice and the audience is what makes art, of any kind, worth doing.